Kabul is grappling with a major water crisis and may become the first modern city to run entirely out of water. Excessive groundwater use has outpaced natural recharge, with aquifers expected to dry by 2030. Pollution, poor infrastructure, and climate change are making things worse, pushing many families into financial distress.

)

A recent report by the NGO Mercy Corps warns that Kabul, the capital of Afghanistan, is at risk of becoming the first modern city to entirely run out of water. Titled "Kabul’s Water Crisis: An Inflection Point for Action," the report highlights the growing severity of the city's water shortage and calls for urgent action both globally and within the country.

The report reveals that Kabul extracts 44 million cubic meters more groundwater annually than is naturally replenished. Over the past decade, the water table has fallen by 25 to 30 meters. Citing UNICEF projections, the report warns that the city’s aquifers could be depleted by 2030, potentially forcing up to 3 million people to leave. The crisis is already severe—nearly half of the boreholes, the main source of drinking water for residents, have dried up.

An aquifer is a layer beneath the ground made of rock, sand, or soil that stores water—like a natural underground reservoir. People draw this water through wells, but if more is taken out than replenished by rain or snow, it can eventually run dry. The report states that Kabul’s water crisis is the result of poor governance, weak humanitarian coordination, inadequate water management, and a lack of proper infrastructure planning. It warns that without urgent action, Kabul could become the first modern capital to completely exhaust its water supply.

Kabul relies heavily on three main aquifers that are replenished by snowmelt from the Hindu Kush mountains. However, recurring droughts and the effects of climate change have led to a sharp decline in both snow and rainfall. Between October 2023 and January 2024, Afghanistan received only 45–60% of its usual winter precipitation. As per the report, Afghanistan ranks as the sixth most vulnerable country to climate change, and Kabul is already feeling the impact—reduced snowfall and shorter winters are limiting the amount of meltwater feeding the aquifers.

Only about 20% of households in Kabul have access to centralised piped water systems. The majority depend on water drawn from borewells, many of which are either unregulated or running dry. According to the report, 90% of the city's residents rely on borewell water to meet their daily needs.

The report also points to serious concerns about water quality. It states that up to 80% of Kabul’s groundwater is polluted with sewage, harmful toxins, and dangerously high concentrations of chemicals like arsenic and nitrates, posing significant health risks.

According to the report, the water crisis is placing a heavy financial burden on Kabul families, with 15–30% of their monthly income spent on water. In many areas, private companies extract groundwater and resell it at steep prices. Weekly water expenses for a single household can reach 400–500 Afghanis ($6–7), often surpassing food costs for over half the population. As a result, 68% of households fall into debt, often borrowing from informal lenders who charge 15–20% interest per month.

Governance challenges remain a major concern. Around 40% of the technical staff at the National Environmental Protection Agency (NEPA), responsible for monitoring water quality, have departed—primarily due to fleeing the country. The agency is unable to carry out comprehensive water testing and lacks essential equipment, largely because of reduced international recognition and funding withdrawals, including from USAID.

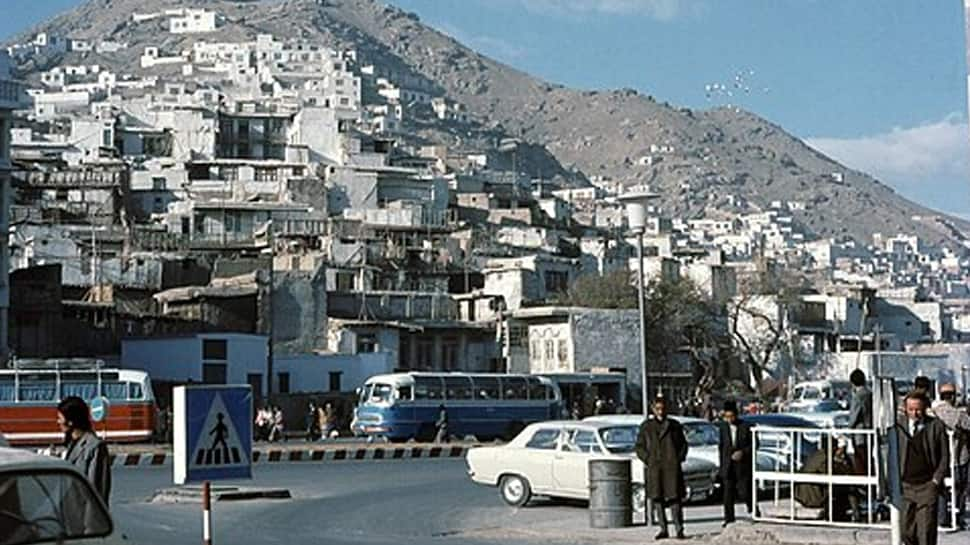

(All images: UNICEF Afghanistan)